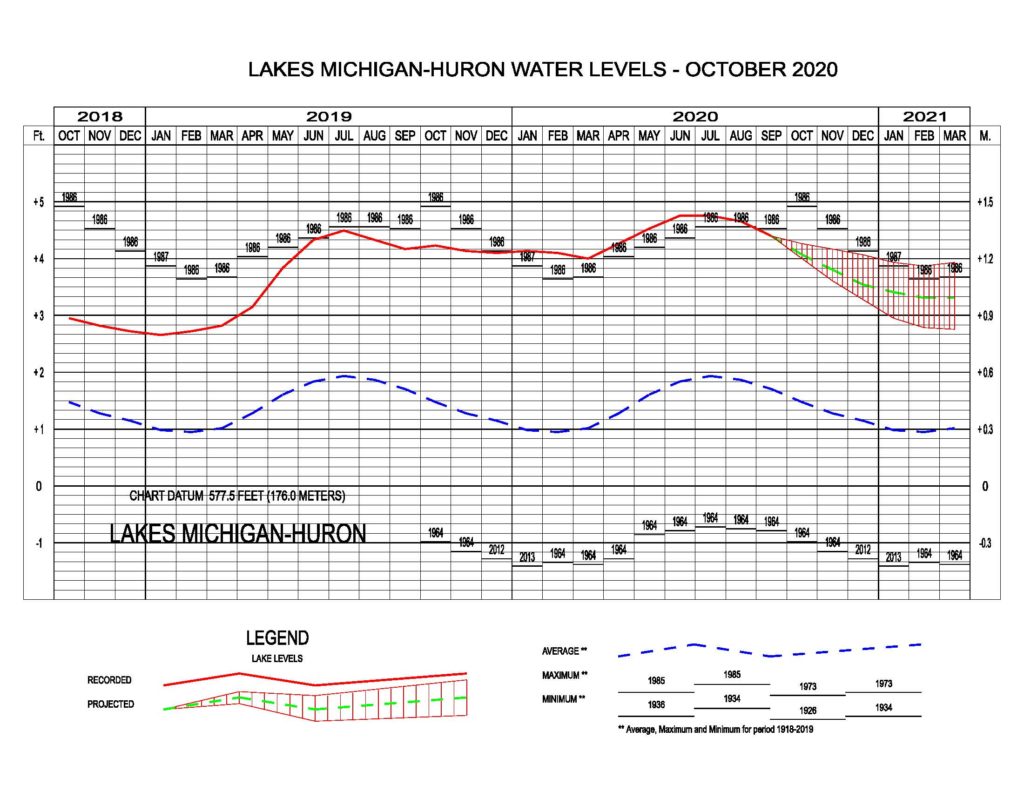

The water levels on all the Great Lakes have finally dipped below their monthly records as of October 9, 2020. Lake Michigan is now 9 inches below the highest recorded monthly average in October previously set in 1986. Additionally, the basin is 1 inch below mean water levels from a year ago. From this point and through the winter, water levels are expected to start their seasonal decline. It is predicted that Lake Michigan-Huron will fall between 2-9 inches from November – March 2021.

Water Levels on Lake Michigan-Huron

Here are five things to know about water levels on Lake Michigan for October 2020.

What are the current water levels on Lake Michigan?

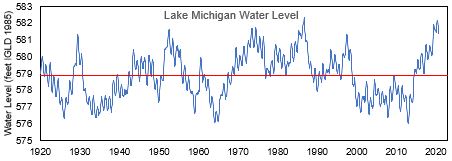

The water level of Lake Michigan as of October 8, 2020 is at an elevation of 581.56 feet above sea level (from the International Great Lakes Datum). To put this level into perspective, here are some statistics for Lake Michigan relative to the period of water level records measured from 1918 to present: (statistics from USACE’s Weekly Water Level Update and USACE’s Water Level Summary.

| Compared to… | Current Water Levels are… |

| One month ago | 4 inches lower |

| One year ago | 1 inch lower |

| Long-term October monthly average (1918 to 2019) | 32 inches higher |

| Record October monthly mean (set in 1986) | 9 inches lower |

What is the outlook for future water levels?

Over the last month, water levels have decreased by 4 inches. The US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) predicts that all lakes will continue their seasonal water level declines throughout the fall and winter (see six-month forecast issued for October 2020 below). Seasonally, this is what we expect: to see a decline in water levels during this time due to evaporation. An increase in water levels generally occurs during the spring as precipitation and snowmelt increase. They tend to level off then decrease at the end of the summer and through the fall as temperatures cool, evaporation increases, and wind speeds pick up. In an average year, water levels vary seasonally by about one foot from a peak in summer to a low in winter, though every year is different. You can read more about this as well as other myths on water level fluctuations on this blog.

Six-month water level forecast for Lake Michigan issued for October 2020. Source: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

What is behind Great Lakes water level fluctuations?

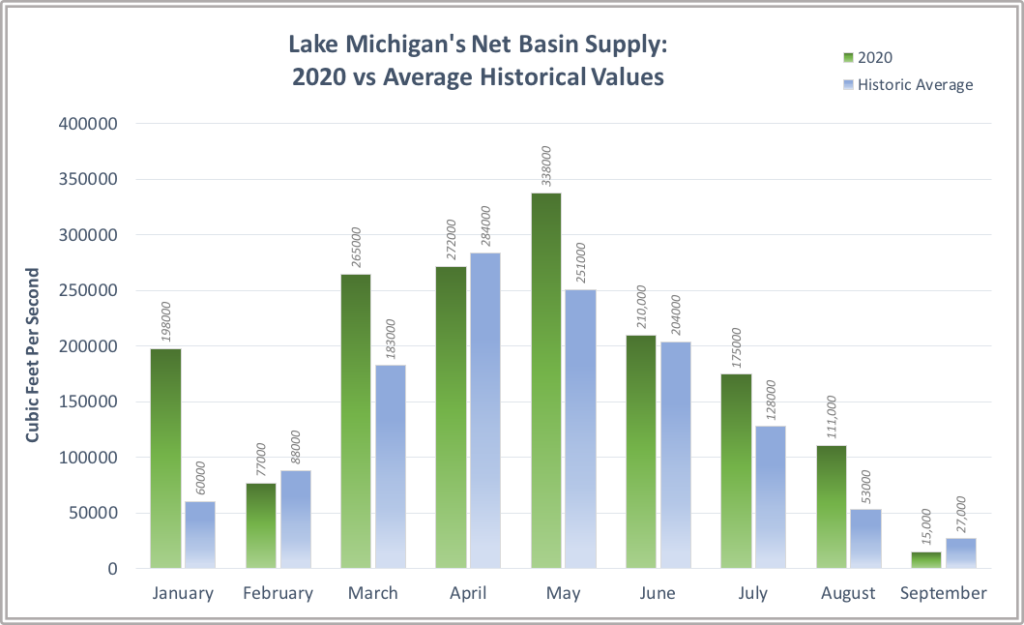

The story of Great Lakes water level changes is told by Net Basin Supply. Net Basin Supply (NBS) accounts for water going into a lake in the form of precipitation and runoff minus water leaving a lake due to evaporation of water from the lake surface. In general, when Net Basin Supply is positive, more water enters the lake than leaves, causing a rise in lake levels. Over the last five years, Net Basin Supply has been consistently positive, driving all the Great Lakes to rise. Click here for more detail.

In September 2020, Lake Michigan water levels declined due to a below-average Net Basin Supply. This was caused by three processes. First, we saw lower than average precipitation (about 18% below average, as measured between 1918 to 2019). Second, the outflows from the Lake Michigan-Huron basin to Lake Erie through the St. Claire River were higher than usual. Lastly, this time of year, as mentioned before, has higher amounts of evaporation than other seasons.

Even though this month’s NBS was below average, Lake Michigan’s NBS for the year 2020 is cumulatively above average. This means that there has, in total, been more water entering the Lake than leaving it compared to a normal year. This cumulative above-average NBS drove Lake Michigan to consistent monthly record highs throughout 2020. So, you can see on the chart below, when the green bar (2020 NBS) is higher than the blue bar (historic average NBS), more water enters the lake than on average for that month (and vice versa). In order for Lake Michigan water levels to actually go down appreciably (beyond just seasonal fluctuations), we would need to consistently see green bars lower than the blue bars.

This image shows a comparison between the current and the average NBS recorded between 1900 – 2008. Calculations based on the Army Corps of Engineers Great Lakes Basin Hydrology for September. https://www.lre.usace.army.mil/Portals/69/docs/GreatLakesInfo/docs/BH-TABLEBOJul20.pdf?ver=2020-07-01-120141-473

What would make water levels go down?

The historic record shows that water levels in the Great Lakes fluctuate between periods of highs and low with changes in precipitation and evaporation, so we know our high water levels will not be around forever. But what are the perfect conditions that would help water levels go down sooner rather than later? According to Keith Kompoltowicz, Deputy Chief of Engineering at the USACE’s Detroit District “A cool, dry fall would evaporate water from the lakes because the lakes are relatively warm. As we move into the winter, we don’t want a healthy snowpack. We want a warm, snowless winter followed by a warm, dry spring. Big picture is that we’re looking at another year of very high and even record high water levels, and the impacts associated with those are going to remain.” Those would be the ideal conditions – low precipitation and runoff with high evaporation – to get a below-average Net Basin Supply which would draw down lake levels. If you are curious to learn more about what drives lake level fluctuation check out this blog on Myth Busting Evaporation on the Great Lakes and other Water Level Fluctuations.

Five places you can find more information:

Our Coastal Hazards page for details about the impacts of high water levels, including erosion, flooding, and navigation issues.

Our Coastal Hazards page for details about the impacts of high water levels, including erosion, flooding, and navigation issues.- Our blog post Resources for Great Lakes Coastal Property Owners: Where do I start? has links to many resources to help

- understand coastal hazards

- weigh the risks coastal hazards pose to property

- understand options for addressing these hazards

- get started on implementing actions if necessary.

- The Great Lakes Water Budgets from the University of Michigan gives more information about what makes the lakes go up and down

- The US Army Corps’ Great Lakes Information page has tons of details on water levels.

- Our Resource of the Month featured here.